Regional

DRC: Tshisekedi’s balance sheet so far

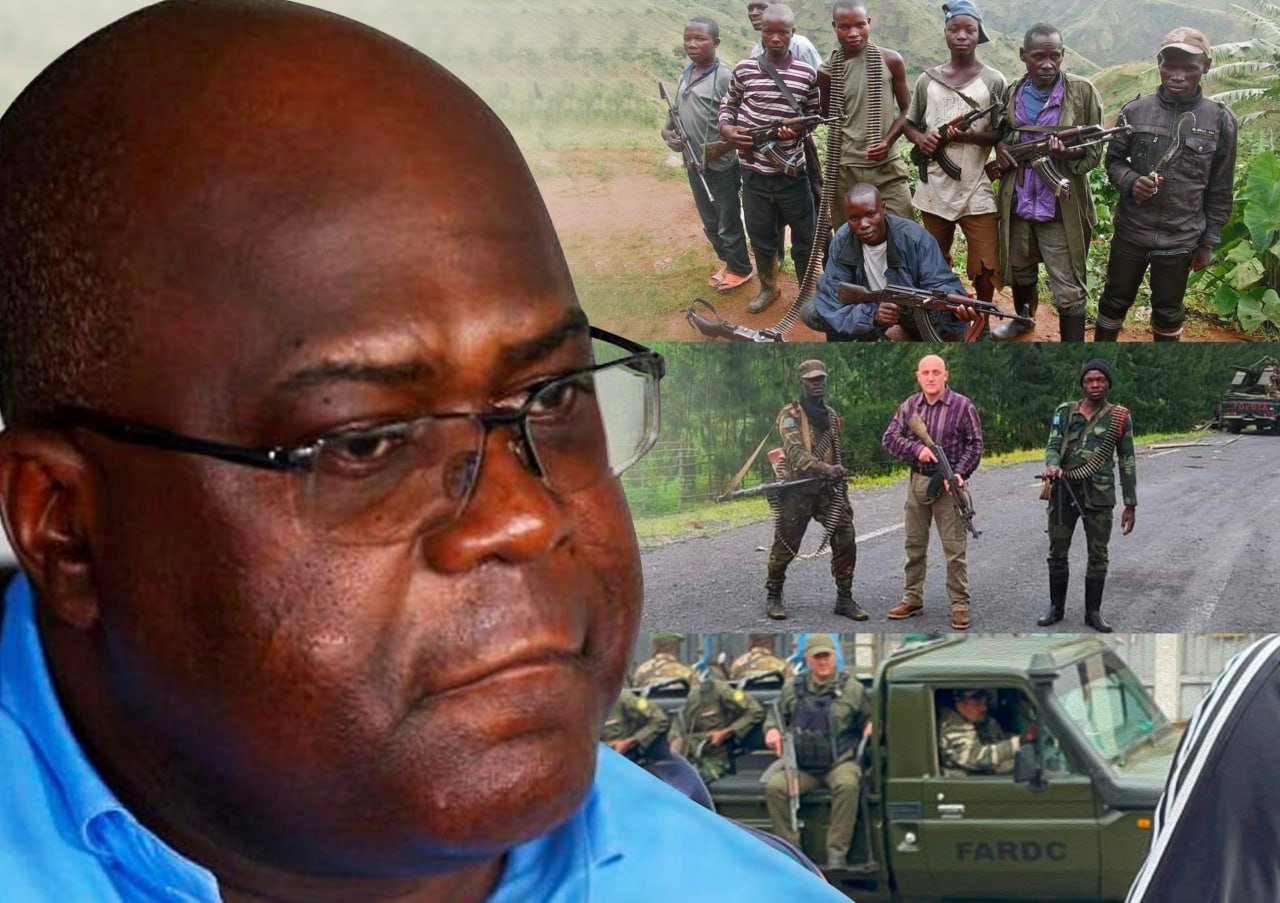

Congolese President Félix Tshisekedi took oath of office at the Palais de Nation in Kinshasa, on January 24, 2019.

The Democratic

Republic of Congo (DRC) is heading for presidential elections in December 2023

where incumbent president Félix Tshisekedi is running for a second five-year term.

Other

key contestants include Martin Fayulu who referred to the 2018 election results

as “a true electoral coup” and proclaimed himself president elect; Moïse

Katumbi, former governor of Katanga Province; and Corneille Nangaa, the former

president of the National Electoral Commission (CENI), who is in exile.

Former

president Joseph Kabila and gynecologist Dr Denis Mukwege are yet to announce their

intentions but it is assumed that they could also be eyeing the Congolese

presidency.

As his

first term is ending, Tshisekedi is recognized for great efforts, decisions and

moves which, unfortunately, were not meant to improve the Congolese’s

wellbeing.

Let’s

first consider the state of affairs in his vast country’s volatile east where

he had pledged to bring peace and stability.

Tshisekedi

initiated a state of siege, in May 2021, in North Kivu and Ituri provinces, where

military authority replaced civilian rule.

Related: Was

state of siege in eastern DRC right approach?

The

state of siege only made the security situation worse.

A large number of indiscipline, corruption, rape, robbery and looting cases have been reported among officers of Congolese national army against civilians who they are supposed to protect.

The state

of siege was extended more than 20 times, with no positive results. Armed

groups increased to over 260, with government officials participating in their

creations.

Related: Tshisekedi

using state of siege to postpone presidential elections

Internally

and externally displaced people keep on increasing, persecutions and lynching against

Congolese Tutsi are ongoing, and women are still being raped by terror groups

including the Rwandan genocidal militia group, FDLR, which the Congolese national

army is collaborating with.

Nangaa

has said that the Republican Guard of the DRC has recruited FDLR elements in

Kinshasa and Lubumbashi.

Tshisekedi

is heavily arming FDLR so that it wages war against the M23 rebels in a bid to

disrupt the rebels’ cantonment process, a part of regional efforts to restore

law and order in eastern DRC through the Nairobi and Luanda peace processes.

Related: DRC:

Tshisekedi heavily arming FDLR, preparing for war

In

addition to refusing to implement different agreements aimed at halting armed

conflicts in eastern DRC, Tshisekedi has been against the East African

Community mission in the area.

After

an Extra-Ordinary Summit of EAC Heads of State on the security situation in DRC

convened in Bujumbura in February, a video clip went viral showing Tshisekedi

humiliating Gen Jeff Nyagah, then

Commander of EAC Regional Force (EACRF).

In

April, Gen Nyagah resigned from the mission, citing “aggravated threat to his

safety and a systematic plan to frustrate efforts of the EACRF” as his reason.

Related: DRC:

What’s the implication of EACRF commander's resignation?

In his

resigning letter to the EAC Secretary General, Gen Nyagah wrote: “There was an

attempt to intimidate my security at my former residence by deploying foreign

military contractors (mercenaries) who placed monitoring devices, flew drones

and conducted physical surveillance of my residence in early January 2023

forcing me to relocate.”

Tshisekedi’s

wish was that the EACRF would fight M23, which was not the Regional Force’s

mission. The latter’s mission was to create a buffer zone, taking over the

localities where the M23 withdraws.

The

EACRF is committed to its mandate and has done a praiseworthy job.

Related: DRC:

EAC Regional Force’s mandate extended, Tshisekedi unsettled

When

Tshisekedi’s expectation failed, he hired Western mercenaries expecting that

their combined efforts with his weak army, the FDLR and other local militias,

would combine to push out the M23 in a short time. This attained nothing other

than escalating violence in the region.

Worse

still, Tshisekedi is cracking down on his strong political opponents using

military intelligence operatives and presidential guards.

A Human

Rights Watch report, in August, pinned Tshisekedi’s government on using the

state apparatus to crack down and arrest opposition politicians.

The

report noted that: “Congo’s justice system and state security agencies –

including the intelligence services, police, and Republican Guard have acted in

a partisan manner.”

Tshisekedi

is again recognized for high levels of corruption.

In

September 2022, leaked videos showed Tshisekedi’s adviser Vidiye Tshimanga promising

to win mining licenses for investors in return for a stake in a joint venture.

“If I

ask [the president] something, he gives,” Tshimanga said.

In

another video clip, Tshimanga was asked who would partner with the investors.

“Me,”

Tshimanga replied. The investor then asked if the president or a minister would

be involved. “Me, it’s the president,” Tshimanga said.

In an

attempt to mask the failures that marked his first term, Tshisekedi has consistently

scapegoated Rwanda, lying to the Congolese that Kigali is behind each and

everything that went wrong in DRC.

On his

March tour in Africa, French President Emmanuel Macron stressed the need for Congolese

authorities to look within for solutions to their security challenges,

especially in the country’s eastern region, instead of always putting the blame

of their challenges on external actors.

“Since

1994, you have never been able to restore the military, security or

administrative sovereignty of your country. It's a reality. We must not look

for culprits outside,” Macron said.

Tshisekedi

fumed.

He knew the world was witnessing the far-reaching consequences of the 2018 electoral fraud.