Regional

For the Catholic Church, punishing genocide crimes is not top priority

For

survivors of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda, the news about

Father Wenceslas Munyeshyaka's ex-communication came to reinforce their view

that the Catholic Church was never interested in punishing genocide criminals.

The Church was only quick to sanction him for

breaching the vow of celibacy as one its priests.

It

was recently reported in French media

that Christian Nourrichard, Bishop of Euvreux, had suspended Munyeshyaka,

priest at Saint-Martin de la Risle Parish for acknowledging the paternity of an

11-year-old child.

Bishop

Nourrichard declared that he was forced to sanction Munyeshyaka, in conformity

with the Canon Law which also stripped him of the right to serve as a priest or

officiate any sacrament.

What

is shocking is that for all those years, the Catholic Church never showed

interest in sanctioning this man for his ignominious past, including

participation in genocide crimes and crimes against humanity which he stood

accused of for more than two decades.

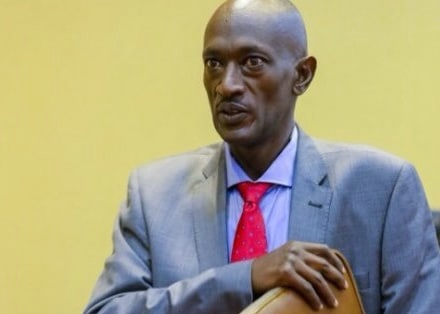

Munyeshyaka

was a vicar at Sainte Famille Church in the heart of the Rwandan capital,

Kigali, during the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi.

He

is accused of taking part in the massacres of the Tutsi at the Centre for

Studies of African Languages (CELA), at Ste Famille Church, St Paul, and the

surroundings. Survivors at Ste Famille also accused of raping Tutsi women.

In

October 2006, Munyeshyaka was tried in absentia before the Military Court in

Kigali as an accomplice of Gen Laurent Munyakazi who had overseen the security

of the city of Kigali during the genocide. According to Rwandan law, civilians

accused of complicity with members of the army are tried before a military

tribunal.

On

November 16, 2006, the Military Court sentenced Munyeshyaka, in absentia, to

life imprisonment.

Between

April and May 1994, Munyeshyaka allegedly contributed to the genocide being

carried out against the Tutsi by the Interahamwe militias and members of the

then Rwandan armed forces. He allegedly repeatedly participated in the

selection of Tutsi refugees to be murdered, left them to die of thirst,

reported to the authorities those who tried to help them and raped several

women.

At

the end of the genocide, in 1994, Munyeshyaaka was ex-filtrated from Rwanda by

the Catholic Church and he went to France where he sought asylum on political

grounds. Since 2001, he was a priest for the parishes of Gisors and the Epte

Valley in France.

A

legal enquiry was opened against Munyeshyaka in 1995 after a complaint was

lodged, for “complicity in torture and inhumane or degrading treatment”.

Witnesses gave account in precise detail of the massive executions which allegedly

took place on the April 17 and 22, 1994 in Ste Famille Church, in downtown

Kigali, where Munyeshyaka was a vicar.

On

July 25, 1995, an official investigation was opened against Munyeshyaka by an

investigating judge, for “genocide, crimes against humanity and participation

in a group already created for, or having as intent the planning of these

crimes, on the basis of the principle of universal jurisdiction as provided for

by the 1984 New York Convention against Torture”.

On

March 20, 1996, the investigation chamber of the Court of appeal in Nîmes

(Chambre de l’instruction de la Cour d’appel de Nîmes) pronounced that France

did not have jurisdiction over crimes of genocide committed abroad, by a

foreigner, against foreigners.

However,

soon after the Statute of the ICTR had come into force under French domestic

law, French Supreme Court (Cour de Cassation), on January 6, 1998, ordained

that the proceedings instituted in 1995 against Munyeshyaka be reopened.

The

case was sent back to the investigation chamber of the Court of appeal in Paris

which, on June 23, 1999, extended the scope of competence of the French judge

to cover genocide and crimes against humanity.

In

September and October 2000, an investigating judge requested that two

international rogatory letters be held in Rwanda to proceed with the hearing of

testimony from around 70 witnesses. By 2004 none of international rogatory

letters had been conducted.

The

slowness of the proceedings led to France being condemned on June 8, 2004 by

the European Court of Human Rights, which had taken up the case in 1999 on the

request of Yvonne Mutimura, one of the plaintiffs in the case.

On

June 21, 2007, the ICTR issued an arrest warrants against Munyeshyaka and

against the former prefect of Gikongoro, Laurent Bucyibaruta, who is also

exiled in France.

On

July 20, 2007, both men were arrested and brought before the office of the

State Prosecutor who sent the case to the investigation arm of the

Investigation Chamber of the Court of Appeal in Paris. This court ruled that

the ICTR arrest warrant was imprecise, especially regarding the French law on

the presumption of innocence and therefore ordered the immediate release of

both men.

The

State prosecutor did not appeal this decision with the result that both men

remained under judicial supervision in the framework of the proceedings already

opened for genocide and crimes against humanity.

The

ICTR issued a second revised arrest warrant on August 13, 2007 and the two men

were again arrested by on September 5,

2007. On September 26, the Court of Appeal in Paris requested further

information from the ICTR stating that it could not decide based on the

information provided.

On

November 20, 2007, the ICTR decided to decline jurisdiction over the case in

favour of the French judicial authorities.

On February 20, 2008, French authorities agreed to try Munyeshyaka and Bucyibaruta in France. Both suspects were arrested, and subsequently released under judicial supervision for the time of the investigation.

On

August 19, 2014, it was confirmed in the report by the International Residual

Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals (IRMCT), that the judicial

inquiry into Munyeshyaka, led by France, was in its final phase.

In

April 2015, the investigation of the case was completed. On October 2, 2015,

the investigating judge ordered the dismissal of the case, in accordance with

the Prosecutor’s request. The judge explained that although Munyeshyaka

manifested radical opinions and had maintained friendly relations with the

military and militias, this would not suffice to establish his participation in

the crimes committed by the militias.

On

November 8, 2017, the Investigation Chamber of the Court of Appeal in Paris

postponed the appeal hearing.

On

June 21, 2018, the Investigation Chamber of the Court of Appeal in Paris

confirmed the dismissal of the case. Civil parties announced their intention to

appeal this decision. On October 30, 2019, the French Supreme Court rejected

the appeal from the civil parties.

Munyeshyaka

is definitively cleared of all charges.

This

was a clear betrayal of the victims and survivors of the mass-killings in the

heart of the capital Kigali in which Munyeshyaka took part.

He

was often seen moving about in bullet proof and armed with a pistol.

It

is difficult to reconcile how, for the Catholic Church, fathering a son is a

heavier crime than being involved in genocide and crimes against humanity.

The

case of Munyeshyaka is a perfect illustration that the Catholic Church prefers

to ignore genocide crimes and crimes against humanity committed by one of its

priests but would not hesitate to punish anyone violating the Canon Law.