International

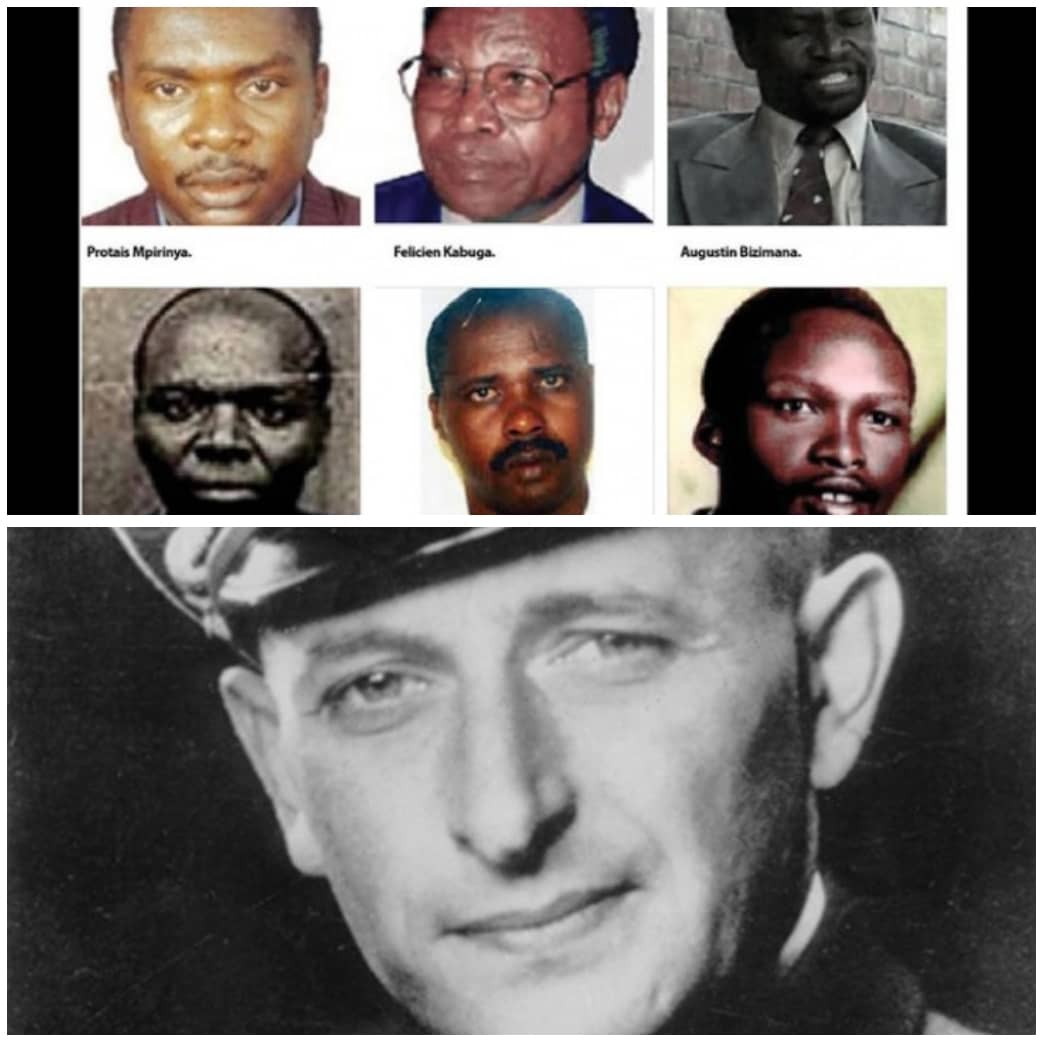

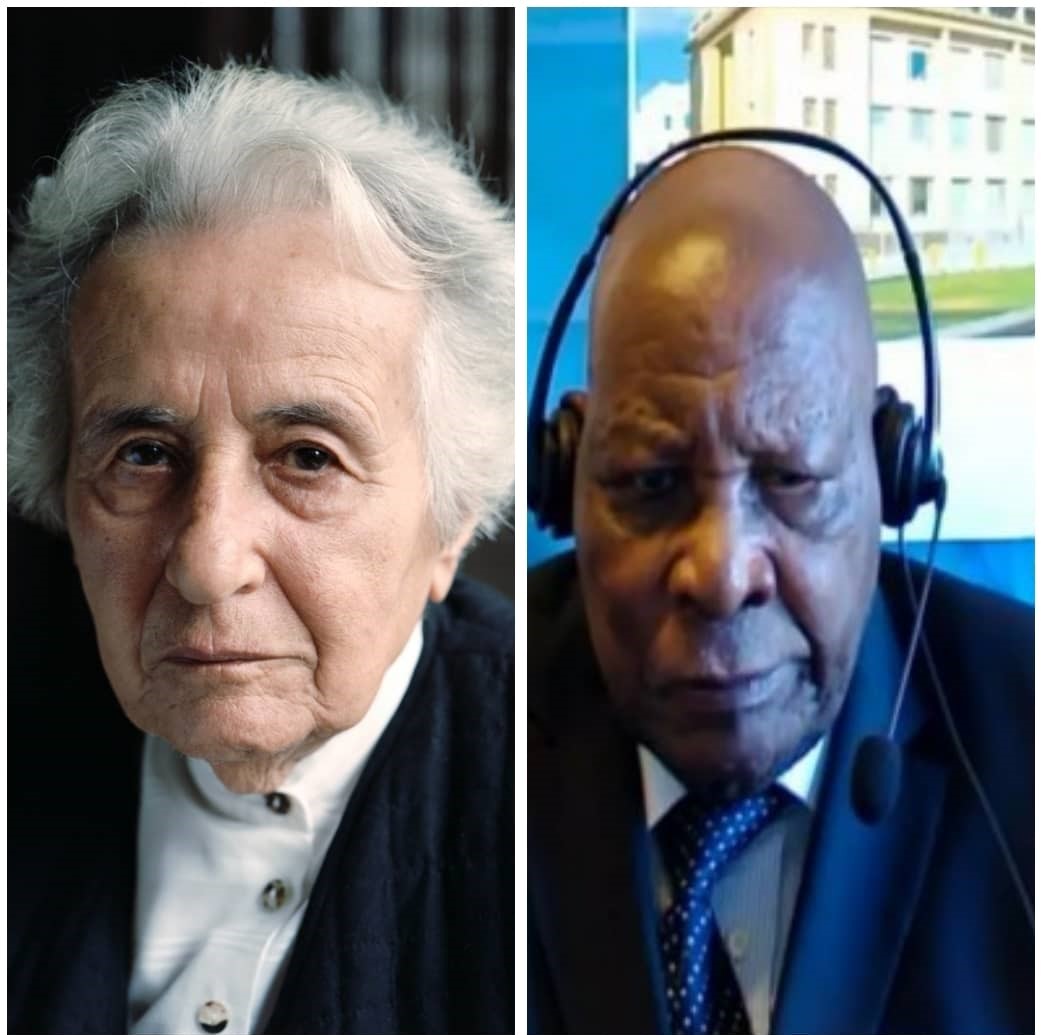

Kabuga and Furchner: None too old to face justice

Irmgard

Furchner, 97, a former secretary who worked for the commander of a Nazi

concentration camp was convicted on Tuesday, December 20, of complicity in the

murders of more than 10,500 people.

Between

1943 and 1945, then-18-year-old, Furchner, worked as a typist at Stutthof

Concentration Camp, in east Germany. Although she was a civilian worker, the

judge agreed she was fully aware of what was going on at the camp. Some 65,000

people are thought to have died in horrendous conditions at the camp, including

Jewish prisoners, non-Jewish Poles and captured Soviet soldiers.

A

statement from the district court in the northern town of Itzehoe in Germany

said the prisoners were "cruelly killed by gassings, by hostile conditions

in the camp, by transports to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp and by

being sent on so-called death marches."

Furchner

was found guilty of aiding and abetting the murders and complicity in the

attempted murder of five others. As she was only 18 or 19 at the time, she was

tried in a special juvenile court, and was given a two-year suspended jail term,

making her the first woman to be tried for Nazi crimes in decades.

Kabuga

Today,

the trial of 89-year old Félicien Kabuga is ongoing at the UN’s International

Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals (IRMCT), in The Netherlands, where he

is being held accountable for his crimes in the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi

in Rwanda.

Arrested

in France, in May 2020, before the court, Kabuga was charged with seven counts,

including five related to genocide; genocide, complicity in genocide, direct

and public incitement to commit genocide; attempt to commit genocide and

conspiracy to commit genocide. Other charges are persecution and extermination

– both as crimes against humanity, all committed between April 6 and July 17,

1994.

Known

as the ‘Genocide financier’, the businessman financed large purchases of crude

weapons including more than half a million of dollars’ worth of machetes used

by killers to kill more than a million Tutsi during the Genocide in 1994.

Kabuga

was a major shareholder of the hate radio station, RTLM, that called upon the

population to massacre the Tutsi. It gave them detailed information on the

people to be massacred and where to find them.

Kabuga’s

atrocities are no different from Furchner’s, if not worse.

In

the ongoing trial, Kabuga’s crimes are slowly coming to light. Before the UN

court, numerous witnesses have pinned him on his role in the atrocities

committed in the Genocide against the Tutsi.

However,

while the trial comes as a relief to many, to Kabuga and his family, the wish

is for the judicial process to be delayed as long as possible. On several

occasions, Kabuga claimed that he is not fit to stand trial, because of illness

and old age. But all his appeals were rejected with medical assessments proving

otherwise.

The

conviction of genocide criminals is a gratification to Genocide survivors,

families of the victims, and it shows that justice can be served. Close to

eight decades, since the Holocaust, Furchner will pay for her atrocities.

This

sets the example that almost three decades after the 1994 Genocide against the

Tutsi, and two years after his arrest, Kabuga will no longer outrun his fate

either, and will also face justice.

.jpg-20221114095304000000.jpg)