Regional

MONUSCO ineffectiveness opens up big questions

Rwanda’s 1994 UN mission no different from MONUSCO

The

eastern region of the DRC has faced security issues for more than three

decades. People there have frequently protested for the UN Organization

Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUSCO) to leave

because its strategy to maintain peace failed.

In

July, at least 12 civilians and three members of MONUSCO, one of the UN's

largest deployments in the world with 14,000 troops, were killed during days of

anti-UN protests. Demonstrators attacked UN bases in at least four cities in

the provinces of North and South Kivu, saying the troops have failed to protect

them from armed groups. Although peacekeepers have been in DRC for 30 years,

they’ve never contained violence from armed groups in the east.

MONUSCO

was deployed to restore peace in the DRC by protecting civilians, facilitating

safe electoral processes and fighting rebel groups. But it has been in the

country for close to 30 years and the opposite has happened. The number of

armed groups has risen to more than 130, people continue to live in unsafe

conditions and innocent lives are being lost despite the presence of UN

peacekeepers.

Local

communities do not have a good relationship with the mission because it has

failed to protect them. Since it was set up in November 1999, the then MONUC – renamed

MONUSCO in 2010 – has proved extraordinarily inept.

There

have been so many cases where the UN mission simply left people to be killed despite

calls for help. On June 6, 2014, Congolese forces and UN peacekeepers failed to

intervene to stop a nearby attack that killed at least 30 civilians in South

Kivu province. At the time, the Congolese army and UN peacekeepers left

civilians in a locality called Mutarule to be slaughtered even though they got

desperate calls for help when the attack began.

The

sad events in DRC, often bring to mind the massacres of more than one million

Tutsi civilians in neighbouring Rwanda in 1994. These people died despite the

fact that a UN mission was posted there. More than a million people were killed

in Rwanda during the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi. After almost three

decades, mass killings are witnessed in DRC where another heavily funded UN mission

is present.

Established

on October 5, 1993, the UN mission in Rwanda was intended to assist in the

implementation of the Arusha Accords, signed on August 4, 1993, to help end the

war and genocide. However, the early months of 1994 saw so many weapons

distributed to the Interahamwe militia in preparation for the Genocide.

The

Belgian intelligence service on March 2, 1994, cited an informant from the then

Rwandan government ruling party, MRND. The informant revealed that Juvénal Habyarimana’s

regime had drawn up a plan for the extermination of the Tutsi. According to the

informant, “If things go wrong, the Hutu will massacre them without mercy.”

Today,

in the DRC, history is repeating itself. Numerous calls are being made for the prevention

of ongoing massacres of Congolese Tutsi, but the UN mission is turning a deaf

ear. People are being killed, girls and women raped and burnt in their houses;

their properties are looted while their cows are hacked to death with machetes.

There is a conspiracy of preparation of a genocide against Kinyarwanda-Speaking

Congolese.

Congolese

government officials continue to use hate

speech to incite violence against Kinyarwanda-speaking Congolese, precisely

the Tutsi community. They have outrightly called for the assassination of

Rwandophones. Government officials

openly mobilized people from other ethnic groups to arm themselves with

traditional weapons and target Kinyarwanda-speaking Congolese. The

23-years-long UN Mission is aware of all these developments but chooses to turn

a blind eye.

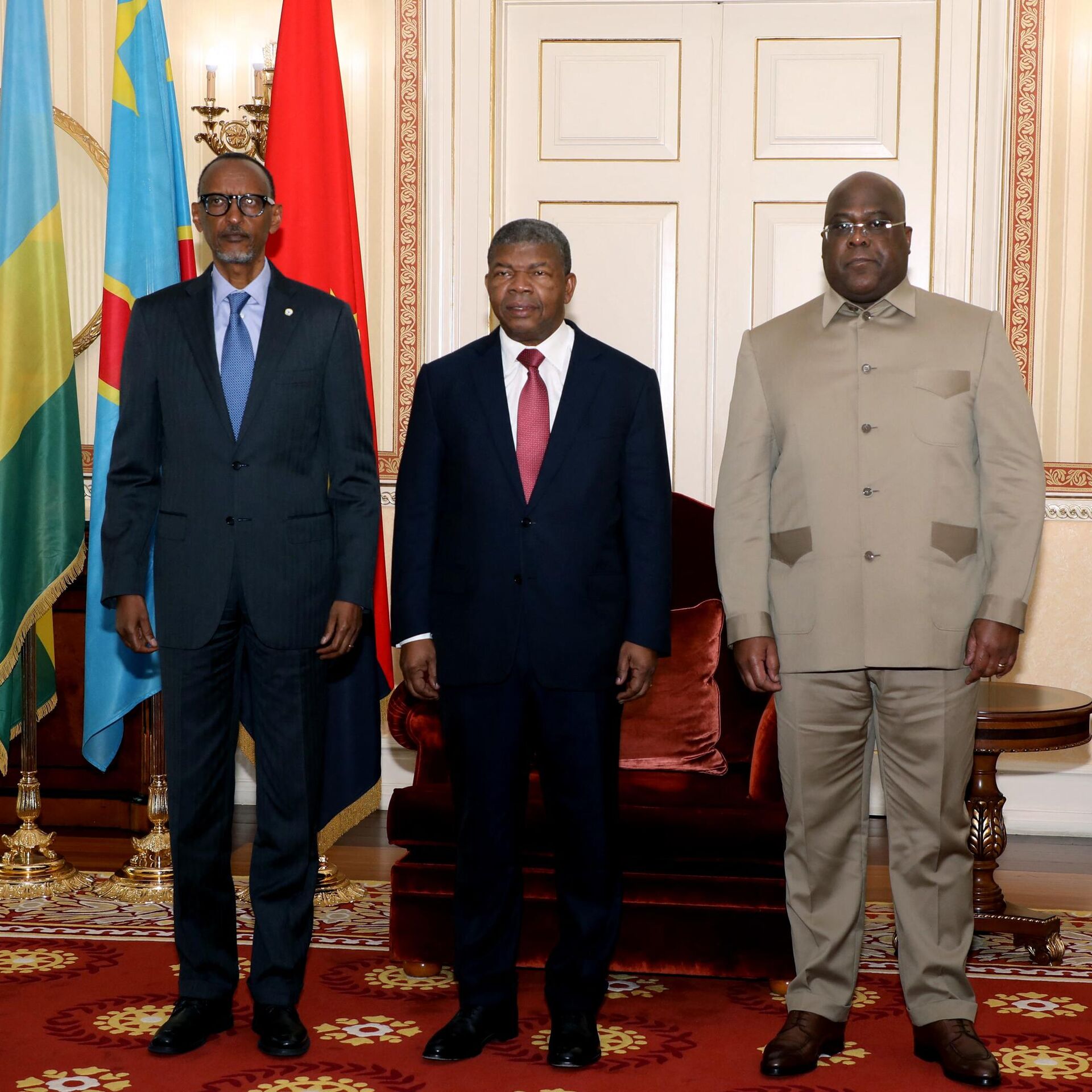

Worse

still, President Félix Tshisekedi, on November 3, issued a call to arms, urging

the country's youth to organize themselves into “vigilante

groups" to support the army.

Vigilante

groups operate militarily just like Interahamwe did. Their main function is not

military defense but causing panic, distress and murdering innocent civilians who

they allege are ‘enemies’ of the state. The alleged enemy, today, is the M23

rebel movement and its Tutsi community in DRC. Even the non Tutsi elements

within the rebellion will be treated as enemies of the state and targeted by

these government backed vigilantes.

In

Rwanda, Interahamwe massacred hundred thousands of Tutsi countrywide during

1990s. Congolese vigilante groups are going to act the same way after being trained

and armed as the UN mission idly stands by.

On March

10, 1994, the UN mission in Rwanda discovered several quantities of heavy

weapons destined for then Rwandan army (FAR) and reported increased recruitment

of Interahamwe militia and military personnel yet provided no positive response

to seize these weapons. In early 1994, Belgium continued trafficking arms to the

FAR despite a United Nations’ arms embargo on Rwanda.

Arms

were purchased through the Angolan rebel movement of Jonas Savimbi, UNITA, went

through Kamina military camp in DRC, to Goma airport, and finally cross the

border into Rwanda through Gisenyi. The UN mission and Western diplomatic

missions in Rwanda were aware of all these channels but never denounced them.

The

same is now happening in the DRC. The Congolese government has purchased war

drones from Turkey to use in battles against the M23 rebellion despite a UN

arms embargo on the country.

As

per UN Resolution 2293 (2016), what is exempted from the embargo are supplies

of arms and related materials, as well as assistance, advice or training,

intended solely for the support of, or use, by MONUSCO or the African

Union-Regional Task Force.

UN

missions are mandated to halt violence and hence restore peace. But, unable to

stop hate speech, civilian killings and arms trafficking in spite of embargoes,

both the UN mission in Rwanda, in 1994 – when more than one million people were

killed – and the current UN mission in DRC, failed.

The

1994 influx of hundreds of thousands of génocidaires from Rwanda

– the Interahamwe – further ignited the spark for the near constant war

and insecurity that has raged in eastern DRC ever since. Despite denials, this

fledgling flame was nursed by the international community.

The architects

of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi, and their genocidal machine, Interahamwe militia

and government forces that had been defeated by the forces of the current

Rwandan regime, poured over the border into Zaire, now DRC. A giant

humanitarian aid camp operation gave these génocidaires the space

and opportunity they craved to regroup, rearm and refinance, in preparation to

return to Rwanda and finish the job - genocide - they were not able to finish.

For

nearly three decades, they have failed to return to Rwanda but they continued

their murderous campaign, and genocide ideology, in DRC under the UN mission’s

watch. Whenever the Congolese Tutsi communities cry out for help, the

international community looks the other way. When the latter pick up arms in

self-defense, they are called terrorists that must be fought, at all cost.