Regional

Kabuga’s case an uncompleted work of justice

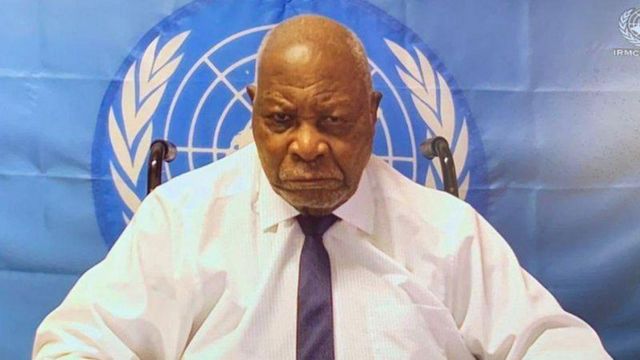

Félicien Kabuga, the notorious financier of the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda, was one of the richest Rwandan businessmen before and during the Genocide.

On September 8, Félicien Kabuga, the notorious

financier of the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda, was deemed unfit

for trial due to mental illness. The decision sent shockwaves through the

international community, leaving victims and survivors of the Genocide against the

Tutsi reeling with a sense of betrayal.

Kabuga, one of the richest men before and during the

Genocide, was a shadowy figure behind the scenes, using his wealth to implement

the plan to exterminate the Tutsi in Rwanda. He purchased the weapons that were used to

exterminate more than one million people.

The world had awaited justice for years, and the

verdict on his mental health felt like an affront to the memory of those who

perished.

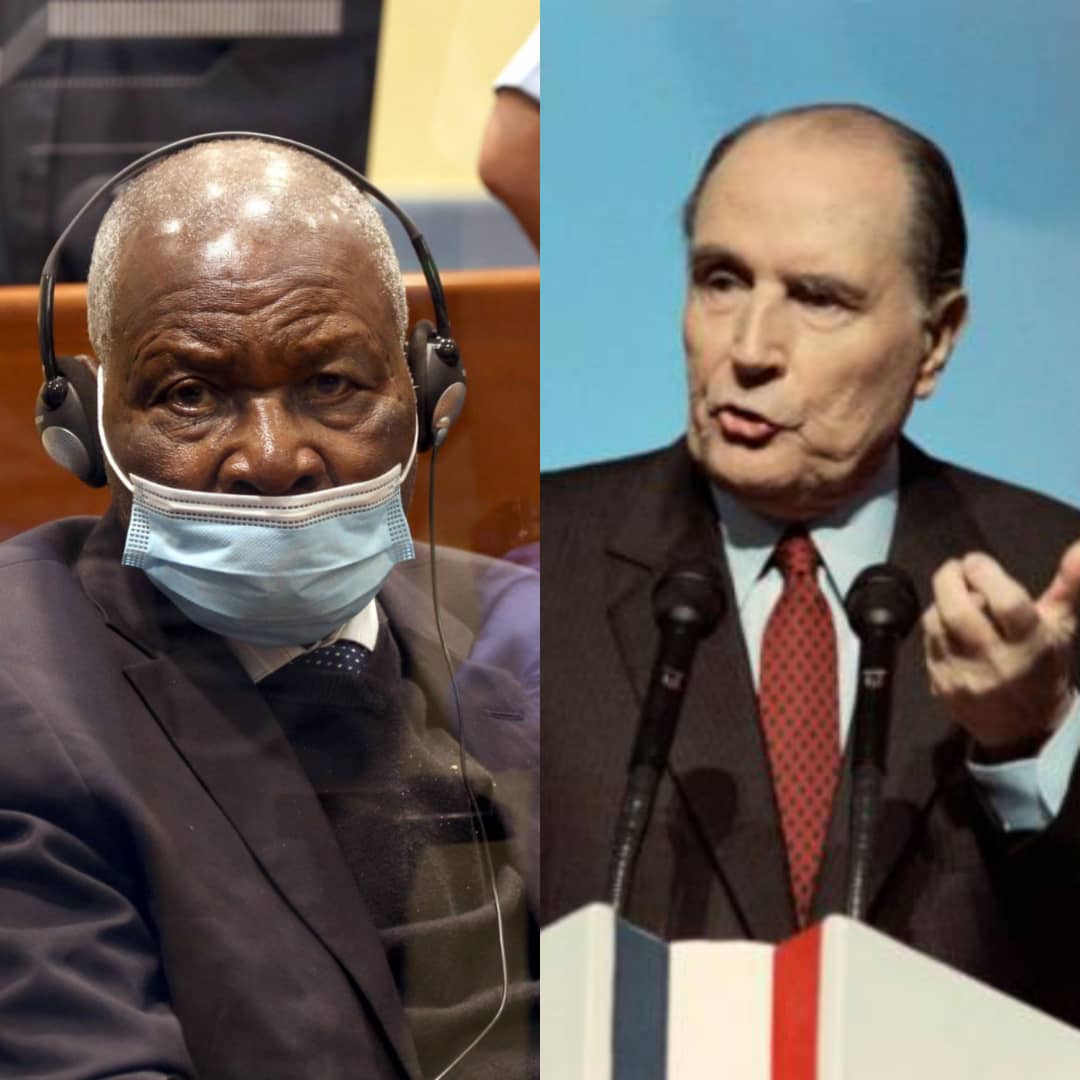

His role in the genocide was not confined to his

financial contributions. Kabuga was among the founders of Radio Télévision

Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM), a genocidal propaganda machine that streamed

hate speech and incited violence against the Tutsi population.

When summoned by the then Minister Faustin Rucogoza in

the beginning of 1994 , few days before the Genocide against the Tutsi to

discuss the venomous rhetoric broadcasted by RTLM, Kabuga brazenly defended the

station, claiming it was merely disseminating the "truth" and could

not please everyone.

This meeting was filmed and was used during the famous

media trial where his colleagues Jean Bosco Barayagwiza and Ferdinand Nahimana

were being judged as they attended the meeting.

Kabuga's name has echoed through the halls of justice

in numerous cases tried by ICTR including the first trial when Jean Paul

Akayesu, former Mayor of Taba Commune was standing for the trial.

Witnesses and survivors had come forward, providing

testimony about his pivotal role in the genocide. Valerie Bemeriki, a woman who

was a journalist of RTLM testified that Kabuga played a key role in RTLM

programmes.

The evidence against him was overwhelming, and for a moment,

it seemed that justice might finally be served. But, that glimmer of hope was

extinguished with the unexpected verdict on the halt of the trial.

In the midst of the despair that followed, a voice of

reason emerged in the form of Judge Mustapha El Baaj. In his dissenting

opinion, he argued passionately that continuing with Kabuga's trial was

"in the interests of justice." Judge El Baaj believed that

accommodations could be made for Kabuga's mental illness while ensuring the

trial proceeded.

However, the Appeals Chamber upheld the decision to

halt Kabuga's trial, leaving many disillusioned. Prosecutor Serge Brammertz

expressed his disappointment, acknowledging that the victims had invested their

hopes in the justice process. He reassured them that it was not the end of

their pursuit of justice.

The international justice system had, once again,

failed the victims. This failure echoed the broader issue of early releases

granted to top convicted genocidaires.

While the world promised "never again" after

the horrors of the Holocaust, the early release of individuals responsible for the

Genocide against Tutsi leaves a bitter taste in the mouths of survivors and

their descendants.

Those who received early release are now active in

denying their crimes of genocide blaming the victims for their own genocide.

This is the case of Capt Innocent Sagahutu, the

butcher of Butare and Gikongoro, who organizes shows on the internet to falsify

the history of the Genocide against the Tutsi. His audience comprises

descendants of Genocide convicts who have a mission to sanctify their parents.

In the aftermath of Kabuga's verdict, survivors

grappled with the sense of injustice that had permeated their lives for nearly

three decades. Their resilience was remarkable, but the wounds of the past ran

deep.

For many, the decision surrounding Kabuga was a stark

reminder that the pursuit of justice to the perpetrators of the Genocide

against Tutsi was fraught with challenges. It raised questions about the

effectiveness of international tribunals and the willingness of the global

community to hold perpetrators of heinous crimes accountable.

As the sun set on another day, they found solace in

their unwavering determination. They knew that the struggle for justice was far

from over, that the legacy of Kabuga would not define their future. In the face

of adversity, they would continue to demand justice for their loved ones, and

for a world that had promised to prevent such horrors from happening again.

The story of Kabuga's escape from justice was a

painful chapter. But it was not the end of the story.

It was a stark reminder to victims and survivors of

the Genocide against the Tutsi that the pursuit of justice is a long and

arduous journey, filled with obstacles and setbacks.

.jpeg-20230127112648000000.jpeg)