Regional

SADC troops won’t solve eastern DRC crisis. Here’s why

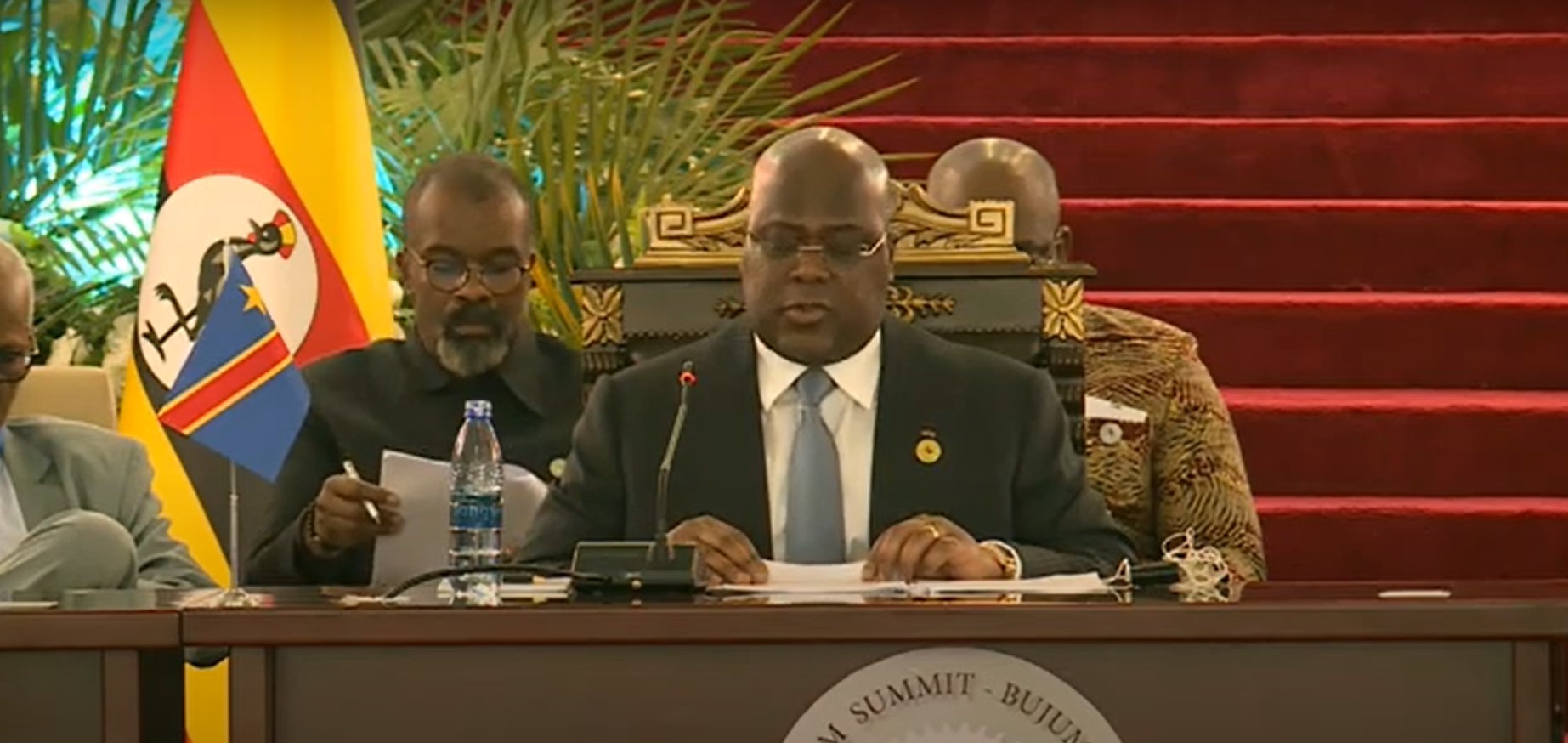

During Windhoek Summit, SADC approves deployment of troops to DRC

The

Southern African Development Community (SADC) on May 8 approved the deployment

of troops to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) as a regional response to

help restore peace and security in the east of the country.

This

was after a meeting of SADC leaders held in Windhoek, Namibia. The SADC summit

“approved a common position to have a more coordinated approach, given the

multiple deployments under multilateral and bilateral agreement arrangement in

eastern DRC,” the SADC Executive Secretary, Elias Magosi, said as he read the

meeting’s communique.

The

summit urged the Congolese government to put in place necessary conditions and

measures for effective coordination amongst sub-regional forces and bilateral

partners operating in DRC.

“We

stand ready, as a region, to address the changing dynamics in eastern DRC,

mainly because of the resurgence of the M23 since last year, the proliferation

of illegal armed groups, some of which launch attacks against civilians, state

security agencies and public infrastructure from neighboring countries,” said

Namibian President Hage Geingob

Geingob

said SADC defense chiefs carried out a field assessment in March 2023 in

eastern DRC.

“The

outcome of the assessment will help us better understand the current situation,

and will guide our interventions, moving forward,” he said.

It

is unclear whether the assessment the Namibian leader talked about actually helped

the SADC bloc to understand the root causes of the M23 resurgence. Were they

even interested in finding the underlying cause of the matter? A lot remains to

be known, or seen.

In

2013, a force from the SADC region – the Force Intervention Brigade (FIB)

comprising troops from Malawi, Tanzania, and South Africa – was embedded within

the UN Mission in DRC (MONUSCO). The FIB had one mission – to fight M23. Ten

years later, the M23 problem resurfaces, or has not gone anywhere. The

rebellion’s resurgence is evidence enough that the root cause of the problem

was never given attention, or properly dissected, and addressed.

By

and large, sporadic waves of fighting across many parts of the country –

especially the east – make the DRC, a country wracked by decades of conflict, a

complex and challenging humanitarian situation. Without a proper diagnosis or

deliberate identification of the nature of DRC’s illness or problem, by thorough

examination of the symptoms, the new SADC deployment will only repeat the same

mistake.

Eastern

DRC already has troops from the East African Community (EAC) deployed there since

November 2022. Under a bilateral arrangement, Uganda also has troops in the

country’s Ituri province. The EAC regional force, EACRF, now occupies numerous positions

vacated by the M23 rebels.

In

March, Angola’s President Joao Lourenço announced that his country would also send

troops to eastern DRC under a bilateral arrangement with Kinshasa.

But,

much as Kinshasa is pestering Luanda and others to deploy, the deployment of

SADC troops in DRC raises more questions than answers, especially since the EAC

already has thousands of troops – from Kenya, Uganda, Burundi and South Sudan –

already deployed in eastern DRC.

What

are SADC troops coming to do that the EAC regional force has not done, or

cannot do? Fight the M23 rebels as Kinshasa wants?

Since

December 2022, the EAC regional force had occupied regions of eastern DRC’s

North Kivu province, which were vacated by the M23 rebels. The rebels were

complying with the Luanda agreement signed in November 2022, so as to give

peace a chance. There was hope as EACRF units moved in and secured territories

evacuated by the M23 rebels as stipulated in the Luanda agreement. The EAC

force now occupies Sake, Kibumba, Rumangabo, Mushaki, Kilolirwe, Kitchanga,

Kiwanja, and Bunagana, among many other areas previously controlled by the

rebels.

The

EAC force’s full deployment permitted the observance of a much needed ceasefire

between parties to the conflict. The EACRF showed it is committed and

determined to the peace and stability process in eastern DRC while upholding

and respecting the DRC constitution, sovereignty and territorial integrity. The

resumption of normalcy was noticeable in all territories after the restoration

of security by EACRF.

Related: Tshisekedi’s

plan to kick out EAC regional force spells doom for DRC

When

EACRF initially deployed, President Félix Tshisekedi expected it to battle the

M23 rebels and push them out of their occupied territories. But war is not what

EAC leaders had prioritised as they wanted political dialogue to come first.

When

his expectations were not met, the Congolese President became hostile to EACRF

to the point of inciting the public and organizing demonstrations against the

regional force.

Related: DRC:

What’s the implication of EACRF commander's resignation?

Eventually,

the then Force Commander of EACRF, Maj Gen Jeff Nyagah, on April 27, bowed to

pressure and resigned from the mission, citing aggravated threat to his safety

and a systematic plan to frustrate efforts of the EACRF.

There

were several attempts to intimidate his security at his former residence.

Among

others, Kinshasa deployed foreign military contractors (mercenaries) who placed

monitoring devices, flew drones and conducted physical surveillance of Gen Nyagah’s

residence in early January 2023, forcing him to relocate.

The

M23 or "March 23 Movement," in reference to an unfulfilled peace

treaty signed on March 23, 2009, between its leaders and the government of the DRC,

is a Congolese rebel group. It was defeated by FIB in 2013 and fled to Rwanda

and Uganda.

The

group that fled to Uganda returned to DRC in 2017 but remained dormant until it

resumed fighting again in late 2021.

The

M23 group is fighting for the safety of its community, the Congolese Tutsi who continue

to face an existential threat. They have been, for decades, marginalized,

discriminated against, and targeted for extermination.

Despite

the available evidence, the international community continues to ignore their

plight.

Following

her official visit to DRC in November 2022, UN Special Adviser on the

Prevention of Genocide, Alice Wairimu Nderitu, was deeply alarmed about the

escalation of violence in the Great Lakes Region where a genocide - the 1994

Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda – happened.

“The

current violence is a warning sign of societal fragility and proof of the

enduring presence of the conditions that allowed large-scale hatred and

violence to erupt into a genocide in the past,” she said.

In

eastern DRC, Nderitu said, the current violence mainly stems from the refugee

crisis that resulted as many individuals involved in the 1994 Genocide against

the Tutsi in Rwanda fled to eastern DRC, forming armed groups such as the FDLR,

which is still active in eastern DRC.

Nderitu

noted that finding a solution to the ongoing conflict in eastern DRC would

require addressing the underlying causes of the violence and learning lessons

from the past.

“The abuses currently occurring in eastern DRC, including the targeting of civilians based on their ethnicity or perceived affiliation to the warring parties must be halted. Our collective commitment not to forget past atrocities constitutes an obligation to prevent reoccurrence”, the Special Adviser stressed.

Has the SADC assessment considered Nderitu’s concerns?

Or,

isn’t the SADC region falling deep into Tshisekedi’s grand deception scheme of

calling the M23 terrorists – in a bid to avoid political dialogue – and lying

that neighboring Rwanda is fanning the conflict in eastern DRC, yet Kigali is genuinely

interested in helping to find a lasting solution?