Regional

Shouldn’t Rusesabagina get fitting sentence as done in the United States?

In

mid-1998, the U.S. Federal Court sentenced

Terry Lynn Nichols to life in prison without parole on the conspiracy charge

and manslaughter of eight federal law enforcement officers killed in the 1995

Oklahoma City bombing.

This American domestic terrorist

was convicted of being an accomplice in the Oklahoma City bombing. He was also tried in Oklahoma on state

charges in connection with the death of other 161 people killed in the bombing.

In 2004, he

was convicted of 161 counts of murder and arson. He was convicted of killing

all the 161 victims and sentenced to 161 life sentences with no possibility for

parole.

Nichols’ sentences, far from being an exception,

are emblematic of how the American criminal legal

system operates. However, these multiple life sentences – or centuries-long jail

sentences without parole – are not unique to the U.S. For example, Spain gave jail

sentences as long as 43,000 years to perpetrators of the 2004 Madrid bombings

that killed 191 people.

Punishment policies vary widely between countries,

and as they correctly put it, in the West they do their things differently. Their

criminal punishment practices, however, would be irrelevant if they could

control their sense of superiority, which drives them to supervise other countries’ institutions

and lecture them on fair trials and human rights.

This entitlement disorder has recently led the

Clooney Foundation, Lantos Foundation, Human Rights Watch, and Amnesty

International to act as supranational jurisdictions with the power and moral

authority to oversee Rwanda's justice system in the Paul Rusesabagina case, while

ignoring for instance Rogel Aguilera-Mederos, a Cuban immigrant, who was

sentenced to 110 years in prison for accidentally killing four people in a

fatal road accident and was only saved by an executive commutation that reduced it to 10 years, exemplifying

the problem of a criminal justice system that is “fundamentally rotten to the core and wildly

antithetical”.

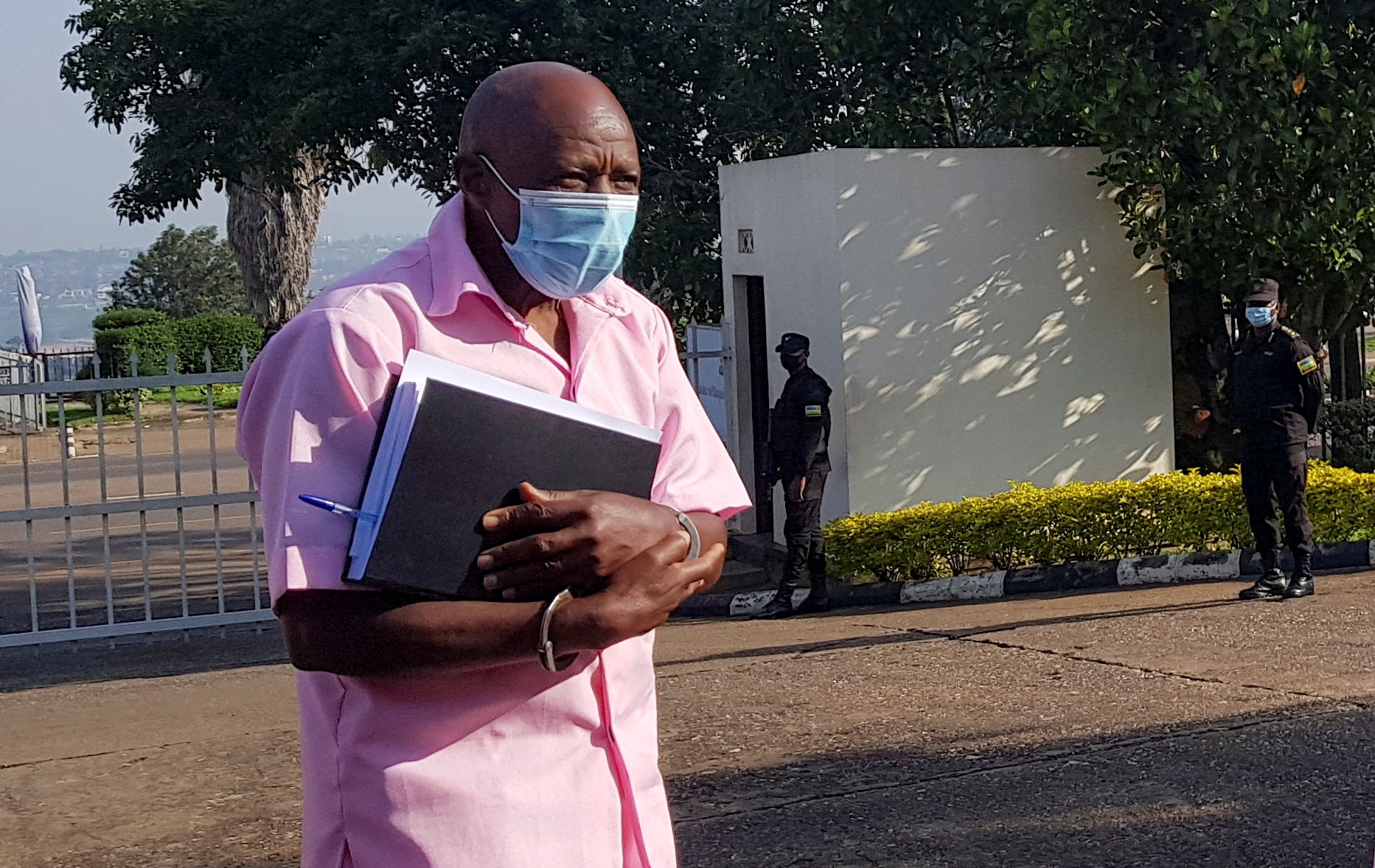

In September 2021, the

US-based Clooney Foundation for Justice (CFJ), which claims to advocate for justice around

the world, described the seven-month court proceedings as a "show

trial", while it argued that Rusesabagina's conviction lacked “sufficient

guarantees of fairness”, and described the 25-year jail term as “likely to be a death sentence given Rusesabagina's age

and poor health.”

The hypocrisy aside, if the

length of Rusesabagina's sentence is a concern, the Clooney Foundation should

be first ashamed of the country in which its headquarters are located.

Second,

as deceitful people occasionally do, the Clooney Foundation inadvertently made

a subtle point that betrayed their efforts to discredit the verdict, admitting

that "the prosecution evidence against [Rusesabagina] was unveiled but not

challenged."

The

main takeaway is that the Clooney Foundation’s contradiction to the

Rusesabagina family's talking point and Western media's decision was to ignore

the truth that was painstakingly laid out in court. The truth always prevails.

Substantial

evidence was laid out in court. It is the reason the prosecution appealed against a number of decisions rendered by

the High Court which handled the case at first instance in September 2021.

Following the completion of the appeal hearings on February 21, 2022 the Court

of Appeal’s verdict was expected to be

read on March 21 but it was rescheduled to April 4 as court sought more time to

go through the case.

While the Court of Appeal is reexamining any material

errors in the trial and considering certain points of law raised by the

appellants, and especially reviewing the prosecution's request to convict

Rusesabagina for all the crimes he committed and sentence him to life in

prison, there are a few things that could be said about how the judge should

decide what sentence to impose.

Article 49 of the Law determining offences and

penalties stipulates that a

judge must determine a penalty according to the gravity, consequences of, and

the motive for committing the offence, the offender’s prior record and personal

situation and the circumstances surrounding the commission of the offence.

In addition, the penal code requirements

– including limits on the length of imprisonment terms – establish boundaries

within which a sentence must fall. Generally, the penal code provides for

mandatory minimum sentences.

In

considering the appropriate sentence in light of those factors, a judge is

bound to impose a sentence that promotes respect for the law; adequately deter

criminal conduct; protect the public from further crimes by the defendant; as

well as provide the defendant with the needed education and rehabilitation

opportunity, or medical care.

These factors, along with aggravating and mitigating

circumstances, ensure that a judge delivers justice.

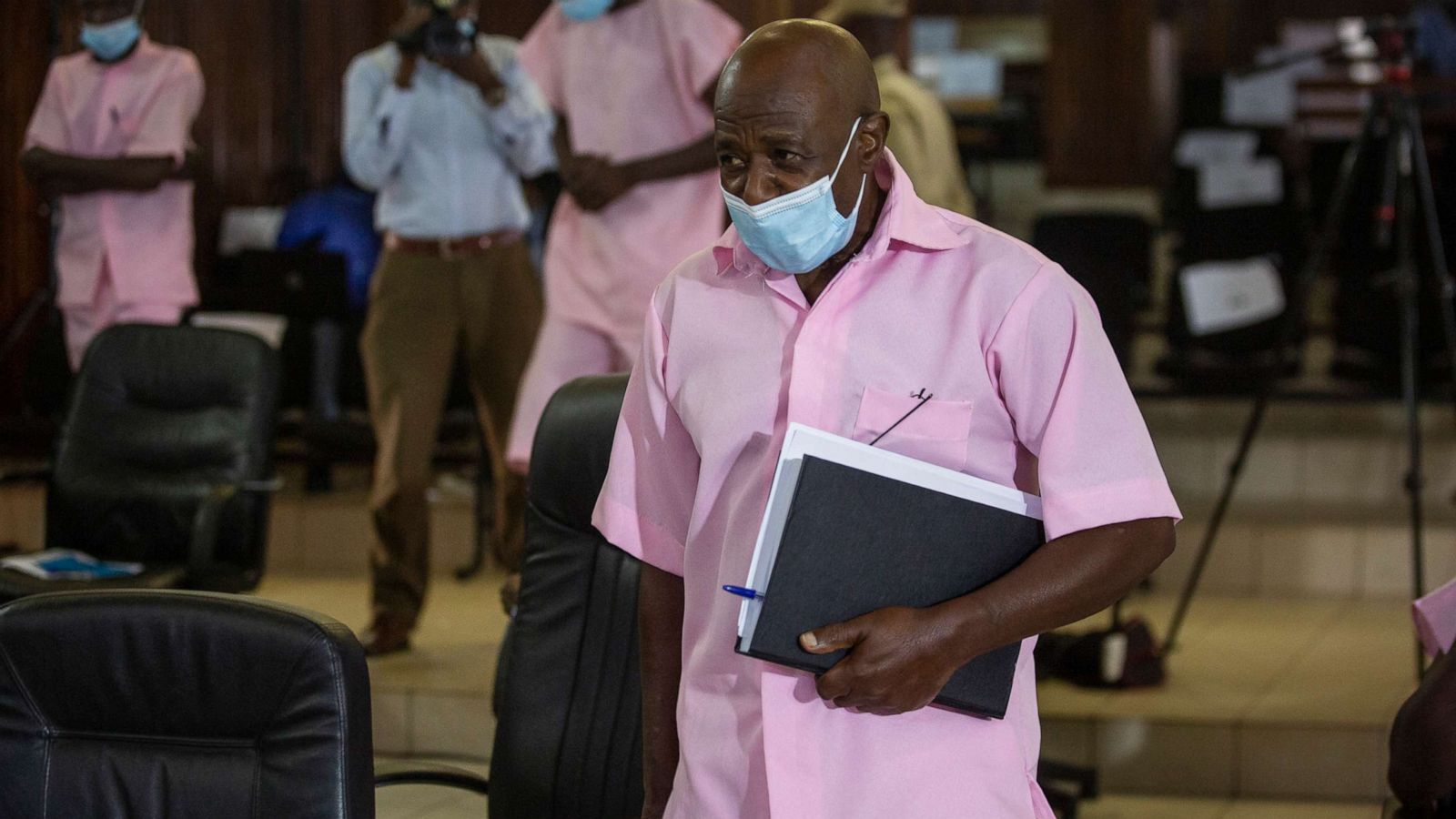

In the Rusesabagina appeal

case, Prosecution protested that the High Court convicted

him only of being part of a terror group as well as committing and taking part

in terror activities. Prosecution argued that not only was there no valid basis

to absolve him of committing terrorism, but there was also no reasonable ground

for not giving him the maximum sentence.

Prosecution asked the Court of Appeal to reverse the

decision of the High Court to redefine and reclassify some crimes. Here, for

instance, charges like the murder of nine people killed in attacks claimed by

FLN as an act of terrorism, kidnap as an act of terrorism, and armed robbery as

an act of terrorism. They were all redefined as one crime of committing

terrorism and taking part in it.

Further to that, the prosecution argued that

Rusesabagina should be convicted of financing terrorism and forming an

irregular armed group as separate crimes, in addition to the crimes for which

he was found guilty by the High Court.

Prosecution questioned the High Court's decision to

accept Rusesabagina's pleas as a mitigating factor, claiming that his

confessions were only partial and that he later recanted his statements.

Prosecution also argued that the fact that

Rusesabagina had never been convicted before should not be a mitigating

circumstance, considering his lack of remorse, the seriousness of his crimes, and

the fact that he was arrested when looking to travel to Burundi to coordinate more

terrorist attacks on Rwanda. All these are

the aggravating factors on which court should have based to hand him a maximum

sentence.

“Prosecution finds that this behavior does not

provide reasonable ground for mitigating circumstances,” reads part of the submissions of the prosecution

to the court.

According to the law, when convicted of being part

of a terror group, a person gets a prison sentence not less than 15 years but

not above 20. When convicted for committing and taking part in terrorism

activities that led to serious effects for example death of people, a person

gets a life sentence.

When reviewing Rusesabagina's sentencing, the Court

of Appeal has a responsibility to ensure that the crimes he is accused of are

not redefined and regrouped, as well as impose the time that fits each crime,

to ensure that the aggregation of sentences for each offence is an appropriate

measure of his criminality, as was done in Nichols’ case in the United States.

This is known as the totality principle in law. This long-standing common law principle. requires a judge who is sentencing an offender for a number of offences to ensure that the aggregation of the sentences appropriate for each offence is a just and appropriate measure of the total criminality involved.