Regional

Why Hutu Power extremism flourishes in France

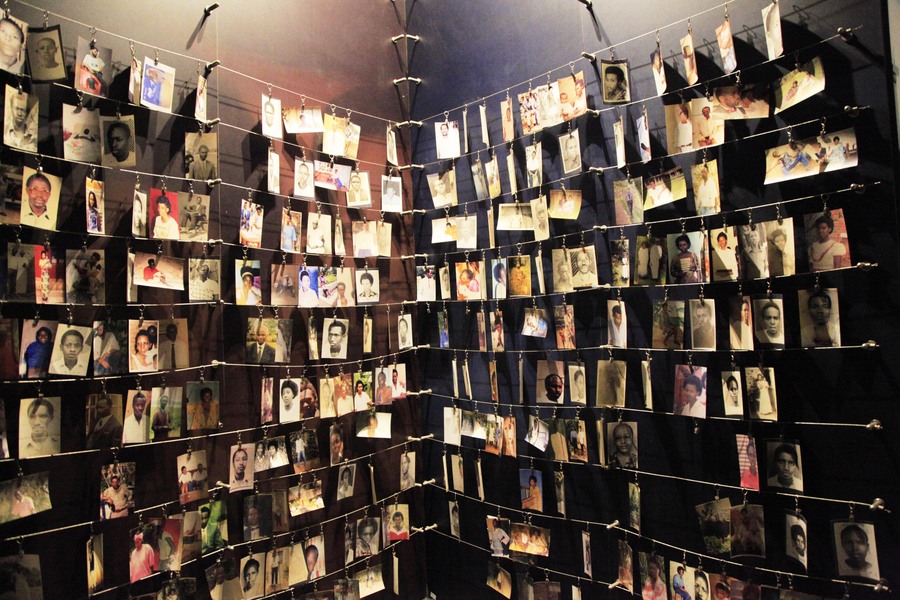

At the end of the Second World War and the Holocaust that

claimed more than six million Jews, Nazis found a haven in Latin America. Similarly, after the war and genocide against

the Tutsi in July 1994, Rwandan genocidaires and their Hutu Power ideology

found safe harbour in France where they have built a stronghold.

In the article “Rwanda: Le “Hutu Power” a Survécu en France »

by Théo Engelbert, published by Mediapart on May 19, light is shed on how

France became a fertile ground for Hutu Power proponents. Mediapart's

investigation reveals the extent to which and how Hutu extremists have, for so

long, thrived in France, in total impunity.

France welcomed hundreds of Rwandan extremists, who

organised themselves in associative networks. Between April and June 1994, more

than one million Tutsi were exterminated in Rwanda. Some of their murderers

today live in France and other foreign countries but only a handful are pursued

or investigated.

According to Andrew Wallis, British freelance journalist,

and writer, “a variety of ingenious methods were used to enter France, their

most favoured destination. One ploy was for Rwandans in Nairobi to head to the

Russian Embassy with a passport, either forged or real, to request a visa to

the Russian capital before boarding a flight to Moscow via Paris. Once in the

French capital, a one night stay allowed the traveller to “disappear”, only to

turn up later and claim refugee status. Others used fake Kenyan passports that

would allow them to travel to Germany that required no visa for Kenyan

nationals. In many cases, families were sent on ahead to the West with the

husband then arriving to claim his entitlement to “family reunification.”

Nobody knows the exact number of those suspected of genocide

crimes. But, in this investigation, Mediapart found out that the prevailing

impunity is particularly incomprehensible regarding three suspects. The latter

are on the first list of persons that Rwanda considers as first category

genocidaires.

According to Mediapart, that list contains the names of

about 2,000 individuals that the Rwandan government wanted brought to justice.

But that list was not exhaustive due the fact it was made in the wake of the

war and genocide. Therefore, there is a strong possibility a lot of suspects

are not mentioned. Mediapart believes

that there is no way the French authorities could have ignored the existence of

that list; since 1996, the administration was aware of it. These are the three

individuals named in the Mediapart report.

Hyacinthe

Bicamumpaka

He was working as a journalist at Radio Rwanda, ORINFOR

(National Office for Information). Two days after the beginning of the

genocide, Bicamumpaka echoed the official version of the justification of the

massacres. This radio commentator justified the carnage of the Tutsi, which was

raging in the capital Kigali, saying that gunfire heard in Nyamirambo was a

result of Rwandan armed forces tracking down the Inkotanyi. As spokesman for

the Minister of Defence a month later, he reminded the population to remain

vigilant for better protection: "on the roadblocks and during the patrols

you do, be cautious and check the identity of all passers-by."

This was a cover for the massacres of Tutsi which was at its

height during that period. In June he told Jeune

Afrique that even if they lost the battle, they would be back. Even if the

enemy wins, he will reign over a desert, he asserted. As indicated by the

Mediapart report, 15 days after this declaration, Bicamumpaka arrived in

France. He applied for asylum in France in 1995, but his application was

rejected in October 1997 because the Geneva Refugee Convention does not cover

people suspected of committing genocide crimes. Surprisingly, Bicamumpaka still

resides in France.

Joseph

Mushyandi

He was a lawyer by training close to the extremist political

and religious circles. He led a puppet human rights organisation. He is

suspected of having attributed to the rebels the massacres perpetrated by the

regime and may have himself participated in the killings in Kigali, his home

region.

He used the tactics known as “accusations en miroir” and worked jointly with individuals who were

condemned to life in prison by international courts. Mushyandi is now the

commissioner of judicial affairs in FDU-Inkingi, a face of PARMEHUTU, whose

members are former politicians who fled from Rwanda after playing a big role in

the Genocide against the Tutsi in 1994.

Anastase

Rwabizambuga.

He worked in the school furniture business in Kigali. He

changed his name in 1999 thanks to naturalisation and resides in

Hauts-de-Seine. The information he submitted for the registration of a business

selling auto spare parts correspond to his details on the 1996 list established

by the Rwandan government.

Mediapart explains that Hutu extremists were able to settle

in France and to enjoy total impunity because of several factors, including the

French authorities' lax and conciliatory attitude towards them. This situation allowed them to invite their

compatriots. The first Rwandan extremists who arrived in France quickly

infiltrated the asylum system apparatus at all levels, central administration,

social services, human rights associations, and even European agencies.

The refusal of asylum to many of these extremists did not

have any judicial repercussions. Mediapart identified 17 people suspected of

having committed crimes by OFPRA (Office Français de Protection des Réfugiés et

Apatrides) but were never pursued. Two died, while three others left France for

Belgium.

But beyond the presence of the three

suspects Bicamumpaka, Mushyandi, and Rwabizambuga, the extremists were able to

set up an association network. Mediapart revealed that those responsible for

the genocide had in fact elaborated a plan that they were following

meticulously. As noted, if the military component of their strategy ended up in

debacle, the setting up of a militant diaspora in Europe was a true success.

After the creation of the RDR (Rally

for Democracy in Rwanda in April 1995, French intelligence services were

initially sceptical about it, then later had a favourable view. One year later,

after its creation, an internal document of the situation of the organisation

reveals in its strategy, RDR planned to create organisations, NGOs, dance

groups which serve as a cover for the collection or transit of funds.

According to Mediapart, while the

RDR was being put in place, Bicamumpaka was busy setting up an association

called Cercle de solidarité Rwandais de

France (CSRF) whose statutes were drawn in Paris by the RDR leadership. This

association in turn blossomed in the four corners of France and created another

15 organisations which were all similar, in accordance with the RDR plan.

Mediapart collected 400 documents showing 279 Rwandans, but this number is not

exhaustive.

Mediapart was able to discover 31

structures in 15 Departments. Their activities are mainly concentrated in

Paris, in l’Essonne, les Hauts-de-Seine,le Val-de-Marne et les Yvelines, mais

aussi à Amiens, Bordeaux, Besançon, Orléans, Le Havre, Lille, Lyon, Rennes, Reims,

Rouen, dans le Tarn, à Strasbourg, Toulouse et Tours. Mediapart noted that

small communities reproduce the social pyramid that existed in the country of a

thousand hills (Rwanda). On the top of the structure, is Rwanda’s former

intellectuals, diplomats, financiers of the military.

Thus,

according to Mediapart, for 27 years,

the Rwandan diaspora in France has been girded by a core of extremists which

chokes any attempt to escape from its control. It is made up of a generation of young Europeans of Rwandan

origin which grew up within the diaspora, moulded in bitterness and lies, and

stepped in the ideology of those who wish to prevent reconciliation amongst

Rwandans at all costs.

Mediapart

concludes that this situation was favoured by the impunity enjoyed by the

genocidaires in France, and the denial sustained by some French political

officials who - for a long time - were engaged in disinformation and

falsification of history. The case of Agathe Kanziga, wife of late extremist

President Juvenal Habyarimana, whose application for asylum in France was

rejected, but lives scot-free in the country, is further evidence of that

impunity.

France

has not been able to extradite her to Rwanda, or to try her in French courts. It

may also explain why Felicien Kabuga, a former Rwandan wealthy businessman who

is dubbed the “genocide financier” who had been on the run for more than 27

years found in France a secure location to evade capture. He was arrested in

May 2020 and is on trial in The Hague, at the International Residual Mechanism

for the Criminal Tribunals.

Months

after the arrest of Kabuga, another key architect of the genocide against the

Tutsi, Colonel Aloys Ntiwiragabo, who served as head of military intelligence

during the genocide was found by Mediapart in Orléans, in central France. Hopefully,

the recent rekindling of the relationships between France and Rwanda, following

the release of two crucial reports, the Duclert Report, and the Muse Report, as

well as the visit of French President Emmanuel Macron to Rwanda marks a turning

point in this sad saga.