Regional

Rusesabagina: Arbitrariness in determining mitigating circumstances violation of fair trial

The Law Nº 68/2018 of 30/08/2018 determining

offences and penalties outlines what the

judge must follow in determining a sentence. Article 49 provides that a judge

determines a penalty according to the gravity, consequences of, and the motive

for committing the offence, the offender’s prior record and personal situation

and the circumstances surrounding the commission of the offence. These factors,

in addition to aggravating and mitigating circumstances, ensure that a judge delivers

fair justice.

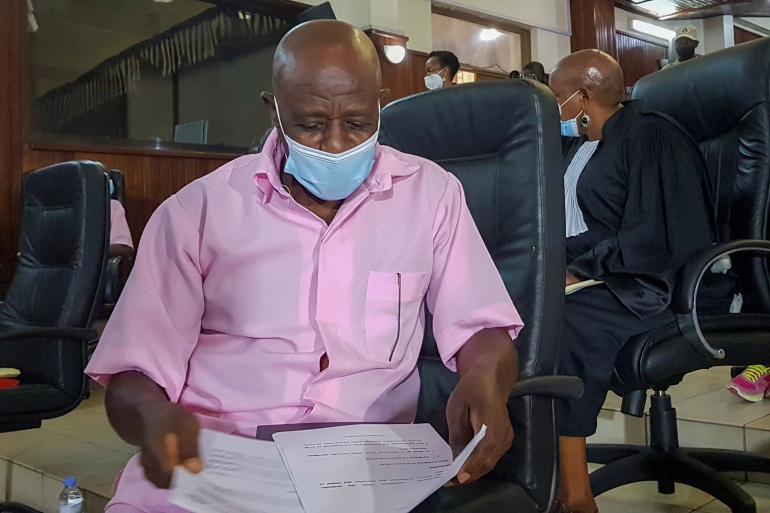

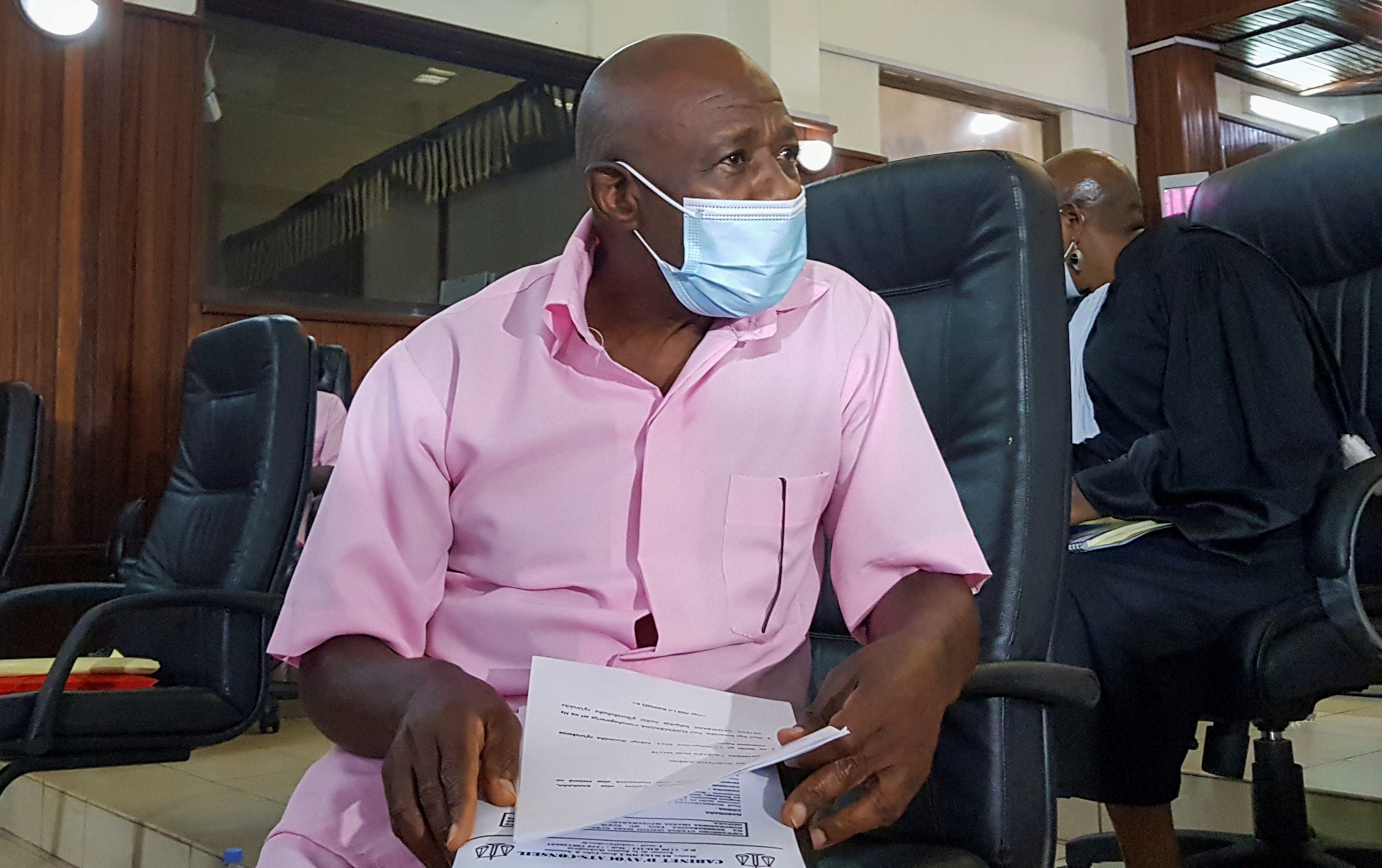

On

September 20, the High Court Chamber for International Crimes sentenced

Rusesabagina and his 20 co-defendants who, as members of the National

Liberation Front (FLN), were accused of terrorism and other charges related to

acts of terrorism that were perpetrated in Rwanda in 2018. Paul Rusesabagina was

found guilty on two charges of joining a terrorist organization and committing

and participating in acts of terrorism. But while the verdict specified that

according to article 37 of the Law Nº 46/2018 of 13/08/2018 on

counter-terrorism, Rusesabagina was liable to life imprisonment because the

crimes he committed resulted in death, he was sentences to 25 years in prison.

In

determining the sentence, the court considered factors that a judge is required

to take into account in determining a penalty, and considered alleged mitigating

circumstances related to the manner the crimes were committed, remorse showed

during interrogations and in bail hearings, as well as lack of criminal record.

The Prosecution

authority, through its Spokesperson, has criticized “the lenient sentences

handed to some convicts”, without

being specific on names. While the

Prosecution is assessing to see if they can appeal, I would like to give my two

cents about the grounds for appeal against the Rusesabagina sentence.

First, on the reason for leniency, article 59 of the

Rwandan penal code recognizes as a mitigating circumstance when a suspect turns

her/himself in, but in the case of Rusesabagina there is hardly any mitigating

circumstance in that regard. He was tricked to travel to Rwanda, when he was

looking to travel to Burundi to connect with his militias to launch more

terrorist attacks on Rwanda.

Second, with regard to the manner the crimes were

committed, the no-harm circumstance requires that Rusesabagina provides

evidence of any measure he took to ensure that FLN attacks would cause no harm.

Even when he learned that FLN terrorist attacks had killed innocent civilians,

he neither dissociated himself from those crimes nor sanctioned his

subordinates responsible of the killings.

Third, with regard to a defendant’s cooperative behavior,

since his arrest in August 2020 until today, and unlike his MRCD/FLN Vice

President, Nsabimana Callixte, Rusesabagina has neither unequivocally accepted

his full responsibility nor sincerely cooperated with justice. Similarly, he has

never cooperated with RIB, the prosecution and the court to assist in

establishing how FLN was funded and how attacks on Rwanda were planned. Instead,

he falsely claimed that he had no role in the armed attacks and lied that he was

only in charge of diplomacy in MRCD.

Fourth, in regard to remorse circumstances, the Court considered

Rusesabagina’s confession to some crimes during the interrogation with RIB. While

the law requires an unequivocal guilty plea and a sincere apology, as opposed

to the half and vague admission made in sworn statements before RIB and in bail

hearings, which he later contradicted by alleging, in an Affidavit by his lawyer,

that he was tortured and subjected to other forms of inhumane and degrading

treatment during the period of interrogation by RIB.

When assessing the judgment and particularly Rusesabagina’s

sentencing, the prosecution should consider how the law defined and qualified mitigating

circumstances in a strict manner, and it set clear standards including requiring

the guilty plea and forgiveness to be sincere (“ushinjwa yireze akemera icyaha mu buryo budashidikanywa”).

These standards are the safeguards from arbitrariness in sentencing,

and disregarding them would also be a violation of the right to a fair trial.