International

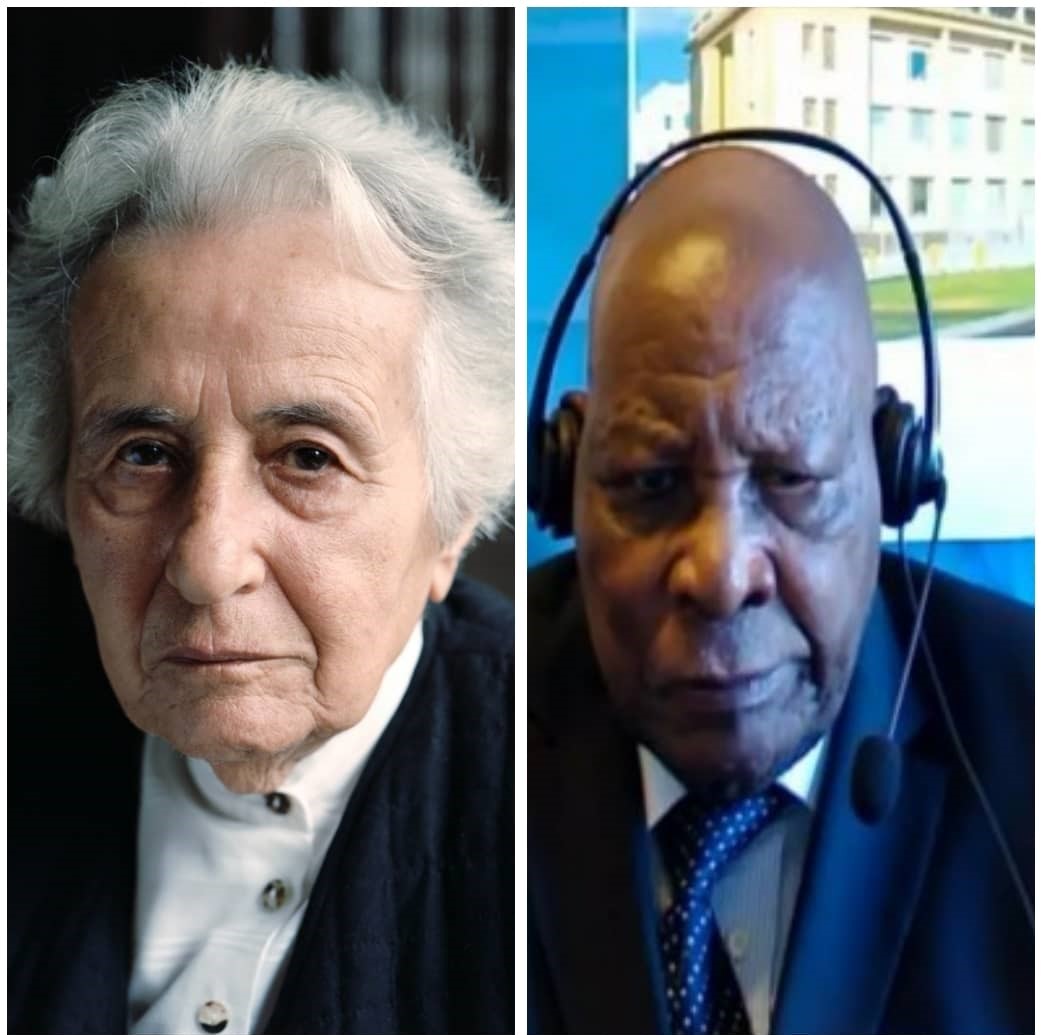

Why trial of facts in genocide suspect Kabuga’s case makes sense for Rwandans

The

decision by the Appeals Chamber of the International Residual Mechanism for

Criminal Tribunals in The Hague that genocide suspect Félicien Kabuga is “unfit

to stand trial” due to deteriorating

health conditions was shocking to Rwandans.

Survivors

of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi were especially shocked that the main

genocide financer will not be held responsible for the crimes of genocide

against the Tutsi. Kabuga, who earlier had a $5 million bounty on his head, was

one of the most wanted genocide suspect. To be released without trial is

abrogation of justice.

It is as

if someone, behind the scenes, prepared a script with details of how the most

wanted genocide suspect would be dramatically arrested after almost three

decades on the run, and how his release would later be played out so that he is

not judged for having played a key role in planning and financing the genocide

against the Tutsi.

Kabuga

is not the first suspect to be deemed “not fit to stand trial” in criminal

justice either genuinely or by faking illness. For a person who has been on the

run for close to three decades and changing identity, after capture, faking

illness would be the expected last resort to evade justice.

The case of Kabuga resembles that of Vincent

Gigante, popularly known as “The Oddfather” in New York and American history,

as one of the most dangerous mafia bosses who feigned insanity for more than three decades to

avoid jail.

Gigante

wandered

around Greenwich Village in his pajamas and bathrobe, talking to parking

meters, and urinating in the street. Psychologists and other mental health

professionals falsely attested to Gigante’s condition, claiming that he had

been in and out of psychiatric hospitals more than two dozen times between 1969

and 1995.

Gillian

Mezey, a professor of forensic psychiatry at St George's University Hospitals

in the UK, said that Kabuga is

not fit to plead, understand evidence, and meaningfully participate in a court

hearing.

Vincent

was a rich man whose criminal enterprise brought in

around $100 million a year.

He bribed his way into feigning madness.

Kabuga was also a wealthy businessman man who used his money to

finance genocide and bribed his way to evade arrest, and when it came, it

played out like a movie script.

Kabuga’s arrest in 2020

in a Paris Suburb of

Asnières-sur-Seine on the third floor in an apartment where he lived under a

false identity mimicked a scene of a Holly Wood movie. French authorities

dramatised his arrest; making it look like he had outwitted UN prosecutors for

decades by using 28 aliases and powerful connections across two continents, as

well as his children, to evade capture.

Kabuga is known to have at least five children,

with two of his daughters married to sons of the genocidal regime’s president,

Juvenal Habyarimana. In just 100 days, in 1994, Habyarimana’s regime, aided by genocide

ideologues like Kabuga, massacred more than one million Tutsi in Rwanda.

When he was arrested, it was hard to believe

that for so many years, one of the most wanted fugitives in the world managed

to live in subterfuge and evade law enforcement across Europe.

Security experts opine that it is hard to

believe that the arrest of Kabuga happened as a surprise to French authorities.

Similarly, Kabuga’s release is cloudy and as suspect as his arrest.

The trial of facts is a process that takes the

place of a criminal trial, with a hearing to determine

whether an accused committed the crimes for which an indictment is issued. Although the trial of facts does not result

in a conviction, in the case of Kabuga, it would be important to determine his

role and responsibility in financing and supporting the genocide against the

Tutsi. Otherwise, his release without determining responsibility leaves Kabuga

an innocent man, hence setting a dangerous precedent regarding providing

justice for the victims of the genocide against the Tutsi.

There is enough evidence, for example, to prove that Kabuga

was the driving force and main shareholder of the hate radio - Television

Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM), which urged Interahamwe militia to hunt and

kill the Tutsi with machetes.

This is

a provable fact whether Kabuga is dead or alive and, therefore, his incapacity

to stand trial cannot stop the court from making a conclusion on the matter

based on available facts and evidence.

The

court has documents showing the names of shareholders in RTLM and the amount of

shares they held. These are facts that can be proved beyond reasonable doubt

and do not require Kabuga to make a personal plea. Another fact that can be

looked at relates to the motive of Kabuga declining to face trial to address charges

against him, but decides to hide for decades under false identity. Why would he

evade justice and change his identity knowing that he is innocent?

The

determination of these facts by the court would provide relief and justice to

millions of Rwandans, who believe that if Kabuga did not sponsor RTLM and use

his wealth to bankroll genocide, the victims of the genocide against the Tutsi

would not have reached more than one million people. Radio RTLM amplified the

hate and hunt for the Tutsi to be killed.

For

the Appeals Chambers’ judges in The Hague to

reject a request by prosecutors for a “trial of facts,” which provides an

alternative procedure, is simply an abrogation of justice.

It is a conspiracy to shield genocide suspects at

the expense of justice for genocide survivors.

.jpeg-20230127112648000000.jpeg)